This article was last updated in 2003 and contains several pieces of out of date information. At the time it was one of the best pieces of research into early episodes of Doctor Who on the web, and as such is presented in its original form as a historical document. Some email and web links are now broken and have not been fixed.

The purpose of this FAQ is to explain the survival of many pieces of rare Doctor Who material, either video or audio, or to explain why the copies of certain episodes that are closest in character to the original broadcast are inadequate for present day use. I have presented it in the form of common questions and answers. I’m keen to hear feedback on this FAQ so please let me know what you think of my efforts! Release dates and catalogue numbers refer to UK releases unless stated otherwise.

Contents

1.0 Introduction

- Why are there episodes missing?

- How many are missing and which episodes are they?

- What steps have been taken to recover material?

- I hear loads of rumours about private film collectors who have missing material but won’t surrender it. Is there a grain of truth amongst them all?

- Did Blue Peter lose The Tenth Planet :4?

- What happened to the viewing prints of The Daleks’ Master Plan sent to Australia?

- How was episode 1 of The Crusade rediscovered?

2.0 Visualising/recreating the missing episodes

- What are these missing episode audios I keep hearing about?

- What are these cine-clips I hear about? How do they differ from normal clips?

- What are the “censor clips”?

- Is it true that nearly six minutes of Galaxy 4: Four Hundred Dawns still exists?

- What other clips exist from missing episodes?

- What are these “behind the scenes” pieces of footage from the sixties and seventies that are referred to by people?

- What are these “telesnaps” and “telesnap reconstructions”?

- What is this trailer from The Power of the Daleks that people mention?

3.0 Existing episodes

- Why weren’t the colour Pertwee stories offered on colour film for overseas sale?

- What prevented the release of The Ambassadors of Death on video at the same time as the other colourised serials?

- The BBC Video release of The Mind of Evil contains a brief extract at the end in colour. I thought the story only survived in black and white?

- Bearing in mind that it’s now highly unlikely colour versions of the black and white only Pertwee episodes will turn up, is there any chance that the black and white versions will be computer colourised somehow?

- What’s this I heard about a colourised version of Invasion Part One being shown at a convention?

- I hear that an episode of Invasion of the Dinosaurs was junked in mistake for a Troughton episode. Is this true and if so, how did the mistake arise?

- Why was it necessary to colourise The Time Monster episode six?

- What is so wrong with The Faceless Ones episode 3 that the print required extensive restoration work for the BBC Video release?

- I hear that the version of The Abominable Snowmen episode 2 released on the BBC Video The Troughton Years is edited. Why is this so?

- I hear that the BBC Video releases of The Time Meddler and The War Machines are edited – is this so?

- Is it true a “slash print” of The Wheel in Space episode 6 exists?

- Are the BBC master copies of The War Games damaged?

- Is it possible to recover a colour signal from a monochrome film recording?

- What is “reverse standards conversion”?

- What is “VidFIRE”?

4.0 Glossary of technical terms used

5.0 Further information

1.0 Introduction

| Author’s note: In some cases I have used what some may see to be “incorrect” story titles when discussing some of the Hartnell serials for which no overall title was given on screen. If you think this prejudices my arguments & that I obviously haven’t done my research properly, you’re entitled to your opinion. But I assure you that the facts contained in this article are as well-researched as possible, and I simply used “wrong” titles because they’re the ones I feel most comfortable with. |

Q. Why are there episodes missing? How many are missing and which episodes are they?

This section is intended both for the reader who may only have heard of the missing episodes phenomenon by reputation and requires more information, and to explain in some detail the roles of various BBC departments in the destruction of material throughout the period of c. 1967 to 1978.

It is tempting to assume that the BBC had an all-encompassing central storage facility at the time it first became necessary to archive Doctor Who episodes (i.e. in late 1963), however this was not the case. 60s (and early 70s) Doctor Who was usually videotaped for transmission and telerecorded from these videotapes for BBC Enterprises, for overseas sale purposes. At this time the only formal archive was the BBC Film Library, whose mandate was to keep programmes made on film. This was interpreted somewhat loosely: for example, episodes such as The Crusade :3 and The Enemy of the World :3 were found when the film library was re-catalogued in 1978. These episodes were originally recorded on videotape but were held by the library as 16mm film recordings, probably because viewing prints circulating through other BBC departments were returned to the film library by default (being film copies) even though they did not originate there, but from the BBC Enterprises master telerecording negatives. (However, as it was filmed rather than videotaped, all four episodes of Spearhead From Space were quite properly kept by the library). The important point is that the library – which is often referred to as “the archives” – did not concern itself with videotapes in any way, as these came under the jurisdiction of the BBC Engineering Department until 1978. (In 1978 the Engineering Dept. videotape library was merged with the film library to become the BBC Film and Videotape Library – Engineering then became Television Recording and ultimately Post Production).

After a sixties programme (for example, Doctor Who) had been broadcast, the master videotape would be given to Engineering, who maintained a small library. They would make a telerecording of it for BBC Enterprises if Enterprises thought it had overseas sales potential (and when colour broadcasts started, copies of the colour tapes that programmes were broadcast from would be made by Engineering, in both PAL and NTSC colour systems, for Enterprises to pass on to the purchasing country). After the telerecordings had been made the tapes would be placed in the Engineering Department videotape library. In about 1967, tapes from the Engineering Department library (for which there was no mandate) began to be wiped to make way for newer programmes, although not until the production teams and BBC Enterprises had indicated “no further interest”. By 1978, so many tapes had been wiped by Engineering that not a single videotape of any Doctor Who story prior to The Ambassadors of Death episode 1 was still held in their library.

The original contracts with the writers, actors and their unions dictated how long BBC Enterprises could sell a programme abroad for – typically 5 to 7 years after its first UK transmission. These contracts also controlled how many UK repeats a programme could have (a great concern on the part of the actors’ union Equity, which in hindsight seems slightly quaint and charming, was that there would be so many repeats that their members would have no new work once technology to record television productions matured during the 1950s). When these rights ran out, BBC Enterprises saw little point in keeping their film copies – they had limited storage space and it seems they thought the Film Library was keeping everything. The Film Library in turn believed that Enterprises was responsible for archival duties and that the Film Library therefore only needed to retain selected episodes of the many BBC programmes produced during their existence. It is unclear how much communication occurred between these two departments and whether Enterprises was aware that they were destroying the only copies of many shows, after the original videotapes were wiped by Engineering. Whilst BBC Enterprises’ permission was needed to wipe the videotapes, once again the extent of internal communication in what must have been a very busy department is not accurately known – since they thought the Film Library was keeping material, Enterprises may not have bothered to correlate the authorisations for tape wiping with their later destruction of the film recordings. Whatever, from about 1972 to 1977, BBC Enterprises destroyed or attempted to destroy all the negatives and prints they had of episodes for which the sales rights had expired.

After the problem came to light (see Is it true that nearly six minutes of Galaxy 4: Four Hundred Dawns still exists?) Sue Malden was appointed as the first BBC Archive Selector – essentially her job was to decide what to keep and what to junk (as things were previously done on a somewhat arbitrary basis), as well as attempting to locate other copies of material that had been destroyed. Malden and Ian Levine were responsible for many early recoveries – the full story of subsequent findings was told in Richard Molesworth’s Doctor Who in the Archives articles in The DWB Compendium and Doctor Who Magazine #257.

As of January 2004, 108 episodes of Doctor Who are classified as “does not exist” in the BBC Archives – the majority of these are from seasons 3, 4 and 5 although some episodes are missing from seasons 1, 2 and 6. A full list of what is missing follows: see Robert Franks’ Doctor Who in the Archives page for more details. In many cases, extracts exist where the complete episode has been lost – Steve Phillips’ clips site has full details of these cases. It should be pointed out that episodes of other BBC programmes were destroyed in a similar way, and also that the BBC was not the only company to indulge in such activities (many ITV companies wiped tapes and destroyed film recordings, leaving gaps in their archive holdings).

| Production code | Story title | Number of episodes | Tx dates (dd/mm/yy) | Episodes missing |

| D | Marco Polo | 7 | 22/2/64 to 4/4/64 | All |

| H | The Reign of Terror | 6 | 8/8/64 to 12/9/64 | 4 and 5 |

| P | The Crusade | 4 | 27/3/65 to 17/4/65 | 2 and 4 |

| T | Galaxy 4 | 4 | 11/9/65 to 2/10/65 | All |

| T/A | Mission to the Unknown | 1 | 9/10/65 | All |

| U | The Myth Makers | 4 | 16/10/65 to 6/11/65 | All |

| V | The Daleks’ Master Plan | 12 | 13/11/65 to 29/1/66 | 1, 3-4, 6-9, 11, 12 |

| W | The Massacre | 4 | 5/2/66 to 26/2/66 | All |

| Y | The Celestial Toymaker | 4 | 2/4/66 to 23/4/66 | 1-3 |

| AA | The Savages | 4 | 28/5/66 to 18/6/66 | All |

| CC | The Smugglers | 4 | 10/9/66 to 1/10/66 | All |

| DD | The Tenth Planet | 4 | 8/10/66 to 29/10/66 | 4 |

| EE | The Power of the Daleks | 6 | 5/11/66 to 10/12/66 | All |

| FF | The Highlanders | 4 | 17/12/66 to 7/1/67 | All |

| GG | The Underwater Menace | 4 | 14/1/67 to 4/2/67 | 1, 2 and 4 |

| HH | The Moonbase | 4 | 11/2/67 to 4/3/67 | 1 and 3 |

| JJ | The Macra Terror | 4 | 11/3/67 to 1/4/67 | All |

| KK | The Faceless Ones | 6 | 8/4/67 to 13/5/67 | 2, 4-6 |

| LL | The Evil of the Daleks | 7 | 20/5/67 to 1/7/67 | 1, 3-7 |

| NN | The Abominable Snowmen | 6 | 30/9/67 to 4/11/67 | 1, 3-6 |

| OO | The Ice Warriors | 6 | 11/11/67 to 16/12/67 | 2 and 3 |

| PP | The Enemy of the World | 6 | 23/12/67 to 27/1/68 | 1 and 2, 4-6 |

| The Web of Fear | 6 | 3/2/68 to 9/3/68 | 2-6 | |

| RR | Fury From the Deep | 6 | 16/3/67 to 20/4/67 | All |

| SS | The Wheel in Space | 6 | 27/4/68 to 1/6/68 | 1, 2, 4 and 5 |

| VV | The Invasion | 8 | 2/11/68 to 21/12/68 | 1 and 4 |

| YY | The Space Pirates | 6 | 8/3/69 to 12/4/69 | 1, 3-6 |

In addition, 13 Pertwee episodes are not held in any transmittable colour format, and only exist in black and white. These are:

| Production code | Story title | Number of episodes | Tx (dd/mm/yy) | Colour episodes missing |

| CCC | The Ambassadors of Death | 7 | 21/3/70 to 2/5/70 | 2-4, 6 and 71 |

| FFF | The Mind of Evil | 6 | 30/1/71 to 6/3/71 | All2 |

| SSS | Planet of the Daleks | 6 | 7/4/73 to 12/5/73 | 33 |

| WWW | Invasion of the Dinosaurs | 6 | 12/1/74 to 16/2/74 | 13 |

| 1 | Colour versions of the outstanding episodes of The Ambassadors of Deathdo exist, however they are unsuitable for colourisation – see later. |

| 2 | Three colour extracts exist from The Mind of Evil episode six, as explained below. |

| 3 | Some fan versions of these stories (especially domestic recordings of North American broadcasts) apparently include colour versions of the missing sections. These are however not real and are created by editing existing colour material together or excising the monochrome-only portions completely and reducing the stories to five episodes in length. |

Q. What steps have been taken to recover material?

When the junking process was stopped in 1977/8, and so much material was found to have been destroyed, various individuals set about looking for other copies of the missing material. Many Hartnell episodes were found in negative form at BBC Enterprises, having been overlooked by the junking teams, whilst other episodes were recovered from overseas TV stations and private collectors. See the aforementioned articles for more details, and also Brian Hass’ Lost and Found Episodes of Doctor Who article. The biggest TV archives (Australia, Canada and New Zealand) have already been searched several times, and material has turned up from TV companies in such unlikely places as Nigeria and Cyprus, but some other companies’ archives have yet to be investigated. For further information on what formats existing episodes are held on and where material has been recovered from, see Robert Franks’ guide. It must be said, however, that the episodes many fans (including me!) would like to rediscover (i.e. the season 5 Troughton stories) are the most unlikely to be found at foreign TV stations as BBC Enterprises paperwork shows they were only sold to a handful of countries (the seminal regeneration pair The Tenth Planet and The Power of the Daleks vying for the wooden spoon with screening rights to each only being sold to three countries). The practice of “cycling” (passing on second hand film prints from one country to another and not obtaining fresh copies from BBC Enterprises) means in reality, fewer copies would have been made from the master negatives at BBC Enterprises. A list of overseas sales rights for each story has been compiled by Richard Molesworth and is available here (Microsoft Word document format but opens fine with OpenOffice). The BBC also started its own “Treasure Hunt” campaign to spread the word, which resulted in a number of recoveries (both television, including two complete series 2 Dad’s Army episodes, and radio) but no Doctor Who material. The main thrust of the campaign is now over but the web page remains open to provide a point of contact with members of the public who may have missing material.

Q. I hear loads of rumours about private film collectors who have missing material but won’t surrender it. Is there a grain of truth amongst them all?

A very old chestnut, this one. Careful research by various people has revealed that many of the rumours circulating in fandom over the years are with only a very slight basis in fact. Such rumours are for example, that a private collector has some or all of The Macra Terror (almost certainly confusion with some amateur-shot clips from this episode, which began to circulate through fandom in 1996) and that William Hartnell was given a print of The Daleks’ Master Plan: The Feast of Steven after it was transmitted (he was actually given a 12 minute portion of The Dalek Invasion of Earth:2 which later found its way to the British Film Institute). One “recovery” often quoted by those advocating such conspiracy theories, is that a poor quality copy of The Tomb of the Cybermen was recovered from “fan” hands shortly after the story was returned from Hong Kong. It must be said that there is no truth whatsoever to this rumour – no redundant copy of Tomb was returned. This is yet another fan rumour circulated by those who fervently believe stories of private collectors hoarding missing material.

The purpose of this FAQ is not to dismiss out of hand every fan rumour of the past 20 years, but to counter suggestions that material exists but is just out of reach, which is not really the case. Private film collectors are a notoriously insular bunch, and it takes some time to be accepted into their circles before they will reveal what they have. Some material has indeed been recovered from private collectors (The Reign of Terror:6, The Crusade:1, The Faceless Ones:3, The Evil of the Daleks:2, The Abominable Snowmen:2,The Wheel in Space:3 and an unedited copy of The Dominators:5) but it seems unlikely that reports of up to 80 missing episodes existing in private hands are true. For a final word on this matter, consider the above list of episodes returned by private collectors. Several of these collectors were interviewed for the 1998 documentary The Missing Years (included on the BBC Video release of The Ice Warriors, BBCV 6387). They all note that the sums they paid for the films when they acquired them were fairly small: less than £20 each. Bruce Grenville, the collector discovered to be in possession of The Lion, was unaware of the value of what he had. Such a body of evidence does not point to organised hoarding as much as simple ignorance (not everyone has a complete list of all missing Doctor Who episodes in their head!) Only the collector owning The Wheel in Space episode 3 attempted to hide what he had, but even in 1984 fan communication was sufficient to pressure him into returning the episode. Another collector did manage to conceal the existence of his unedited prints of The Time Meddler episodes 1 and 3 for some years until finally returning them in the early 1990s but this is very much the exception that proves the rule. In addition, the standard law of conspiracy theory would appear relevant: the greater the number of people involved in a conspiracy, the more likely it is that someone will leak the details of the cover-up. Of course, one can never conclusively prove a negative, but the available evidence does not support the concept of “missing episode clubs”. Readers may also wish to note that rumours of greedy collectors hoarding episodes of The Savages or The Space Pirates are conspicuous by their absence!

Q. Did Blue Peter lose The Tenth Planet episode 4?

There is a long-held belief in fandom that the fourth episodes of The Daleks’ Master Plan and The Tenth Planet were stolen from the Blue Peter office in November 1973. The evidence for this is thin: certainly The Traitors (Master Plan :4) was signed out from the BBC Film Library for Blue Peter to use clips from in the episode transmitted 5th November 1973 (celebrating 10 years of Doctor Who), and despite repeated memos to the person who signed the episode out (who went by the name of J. Smith – this could have been Justin Smith, a member of the Blue Peter production team whose responsibilities would have included ordering up such materials) the print was never returned to the Film Library. The Tenth Planet episode 4 must have been obtained from BBC Enterprises – there is no evidence that the Film Library ever had a copy of the episode. Furthermore, Enterprises were continuing to sell the story abroad until 1974 (although this does not necessarily mean that the print of episode 4 was returned to them after Blue Peter had finished with it; they would have retained a master negative to strike new prints from, before this and any other copies of the episode they held were destroyed when the sales rights ran out). It is unlikely that episode four of The Tenth Planet would have been taken to the Blue Peter office; more likely it was taken to a central telecine area where the clip of the Doctor regenerating was copied from a film print to an insert tape for the episode of Blue Peter (by examining the noise characteristics of the clip, such as the areas of the picture that show sparkle, we can be fairly certain that the clip was taken from a print and not the master negative of the episode). Hence, if it was never in the Blue Peter office, it could not have been stolen from it! This is an example of how fan rumours can take a known fact and compound the slight mystery surrounding it, to suggest something that was not in fact the case is a certainty. The BBC Film Library had obtained viewing prints of episodes 1 to 3 which were all accounted for when the library was catalogued in 1978 – these are the copies which exist today. Episode four was not amongst the films in the library in 1978, but there was no expectation that it should have been – the only episode which was unaccounted for after the cataloguing operation was The Traitors. What happened to the prints used to take the clips is not known – they could indeed have been stolen, however it is more likely that they were never returned and were destroyed by the telecine department.

Q. What happened to the viewing prints of The Daleks’ Master Plan sent to Australia?

Viewing prints of 11 episodes of The Daleks’ Master Plan (the missing one being the episode broadcast on Christmas Day 1965 in the UK, The Feast of Steven) were sent to ABC Television in Australia, for them to evaluate them prior to purchasing the story. Strict censorship laws were then in force in Australia (see What are the Censor clips?) and hence the episodes first had to go before the Australian Film Censorship board for review. This was done on 13th September 1966 and the Board’s judgement was “These episodes not classified, see files for information.” A further comment was typed onto this memo:

These episodes were all considered unsuitable for TV ‘G’ [as in “general” rating] not because of specific scenes, but because of their storylines. The importer [the ABC] therefore elected not to attempt reconstruction, and the episodes were not registered.

While it has been assumed that the episodes were either destroyed or returned to the BBC, investigations are currently in hand to determine exactly what did happen to these viewing prints sent to ABC TV. Unfortunately, although a paper trail was found, it seems likely (late 2003) that the film recordings sent to Australia do not exist.

Q. How was episode 1 of The Crusade rediscovered?

This episode was returned to the BBC early in 1999 and was released in mid-1999 on a special BBC Video release (BBCV 6805, released July 1999) together with all four episodes of The Space Museum. The episode was actually discovered in the care of a New Zealand film collector by a prominent New Zealand fan, Neil Lambess. Later, Neil contacted Paul Scoones who arranged for it to be returned safely to the BBC for them to make a copy. The full story of how the episode was discovered is told in issues 17, 18 and 19 of The Disused Yeti newsletter and Steve Roberts describes the work undertaken to clean up the recovered print in his Restoration Team pages.

2.0 Visualising/recreating the missing episodes

This section deals with the ways in which it is possible to get an idea of what a missing episode was like, from other material that might exist pertaining to the episode in question (such as the soundtrack, clips or amateur-shot footage of the making of the episode).

Q. What are these missing episode audios I keep hearing about?

During the original broadcasts of the Hartnell and Troughton episodes, some more dedicated fans would place their reel-to-reel tape recorders near the TV speaker and record the soundtrack of the episode (it should be noted that, although primitive sets did exist, home video recording was almost unheard of at this time). Bearing in mind the quality of the components making up both the TV sets and the tape recorders, it is not surprising that the sound quality of many of these recordings is absolutely awful! Some of the best quality recordings of this type came from the collections of fans like James Russell and Richard Landen, and were used by the BBC for the release of their four Doctor Who — The Missing Stories audio tapes. These were The Evil of the Daleks (1992),The Macra Terror (1992) and The Power of the Daleks/Fury From the Deep (both released in 1993). None of these tapes are still available in the UK, and only the first two were released in the US. In addition The Tomb of the Cybermen (audio provided by David Stead) was prepared for this series, narrated by Jon Pertwee; however before it could be released the film recordings of the serial were returned from Hong Kong and the story was released on BBC Video. The audio version was released in 1992 due to contractual obligations with Pertwee but was not marketed as part of the same series as the other releases. Most of the audios in fan circles for years consisted of recordings beginning with The Daleks’ Master Plan. For many years audio recordings of the missing portions of The Reign of Terror, The Crusade and Galaxy 4 were simply not known to exist. (A very poor quality copy of the audio track to Marco Polo was known about, held by Richard Landen, who did also have complete audio recordings of The Crusade and Galaxy 4 but had kept them back as potential bargaining ammunition).

A major breakthrough came in 1994, when a fan called Graham Strong approached the BBC with very high quality audio recordings of most episodes from The Daleks’ Master Plan:Volcano (episode eight) to The Dominators. There are several gaps in the Strong collection – these are The Daleks’ Master Plan episode 11 (The Abandoned Planet),The Celestial Toymaker (which Strong thought at the time was “a silly story”) and The Gunfighters. Strong had actually taped Doctor Who right from the first episode, albeit with a cheap second-hand tape recorder which did not have a good quality microphone, but later wiped most of his early recordings for re-use (three episodes survived unwiped, but they are of poor quality and are of existing episodes anyway; namely The Sea of Death (The Keys of Marinus:1), Strangers in Space (The Sensorites:1) and The Space Museum (The Space Museum:1) although part of World’s End (The Dalek Invasion of Earth:1) also survived). He had also approached the BBC before about his recordings, when the hunt for missing episodes was at its peak, but had been told that they were only interested in video material at the time. Later however, the newly-formed Doctor Who Restoration Team became interested and borrowed Strong’s tapes, which were transferred to DAT (Digital Audio Tape) by Paul Vanezis and are retained by the BBC for future use. The quality of Strong’s recordings is so high that some are even superior to the soundtracks on the telerecordings of existing episodes held by the BBC, and his recording of The Tenth Planet episode 2 was used to redub the film print. This quality stems from the fact that Strong had a good quality tape recorder (which he bought early in December 1965) and he discovered a way to connect his tape recorder directly to the television, thus producing the recordings of outstanding quality that became known as the “crystal clear” recordings.

This still left early stories either with no audio at all known to exist or only very poor quality copies. The final gaps were plugged in 1995 when another fan, David Holman, came forward with his own high quality recordings of many episodes. Holman began recording Doctor Who with Marco Polo using a good quality microphone (and managing to keep the other people in his house quiet for nearly a year’s worth of Saturdays!). He continued to record well after Strong had lost interest and it is believed his collection extends up to The Three Doctors. Whilst the quality of his recordings was not as high as Strong’s they were far superior to the other copies of some episodes, particularly Marco Polo. Some small problems were found with Holman’s recordings: he had edited the episodes together into compilations, and quite often parts of an episode just after the overlap sections would be missing and must be patched in from other (poorer quality) fan recordings before the audio of the complete story can be released. It is assumed that Holman did this to make the stories “flow” better – it seems unlikely he was trying to save tape as several of his reels have a few blank minutes at the end. Some of his episodes were also recorded too loud and some distortion occurs, however this can be overcome with modern digital technology. Holman’s collection included The Crusade and Galaxy 4 as well, and so the current, very fortunate state of affairs was reached, whereby high quality audio recordings of all missing Doctor Who episodes are known to exist. The Restoration Team also borrowed Holman’s tapes to allow the BBC to have copies.

In the years since the initial rediscovery of these audio recordings other fans have taken both sets of recordings and have increased the sound quality even further using the latest digital technology. Some problems still remain as artefacts of the time when the recordings were made; for example Strong’s recording of The Massacre :4 suffers from highly variable sound levels towards the end of the episode caused by interference from a French radio station (Strong lived in Exeter at the time, and such interference could cause problems at certain times of the year). This fault was successfully overcome by Mark Ayres for the BBC Radio Collection release of the story in August 1999. One thing that should be cleared up however, is that Holman and Strong recorded every episode of Doctor Who (with the exceptions listed above) during the periods they were taping the show. They didn’t magically predict which episodes would be missing in 30 years’ time and only record them! Of course, only the recordings of episodes no longer extant in the BBC archives are of interest (with a few exceptions such as the aforementioned Tenth Planet:2) as, although the quality might not always be as good, it is far simpler to use the soundtrack of the film prints for episodes which do still exist. One further use of the audio recordings is to dub over clips which are either silent or have an incorrect soundtrack (some clips from The Power of the Daleks episodes 4 and 5 fall into this category) or to help in the restoration of material known to be missing from prints of episodes recovered from overseas (as in the case of the BBC Video release of The War Machines [BBCV 6183, released June 1997]).

Most recently audio recordings made by other fans (David Butler and Allen Wilson) have come to light. They are of similar quality to Holman’s recordings but not edited together so the recordings are more complete. Butler would often record only record one or two episodes from a serial as he notes:

“…cost prevented me from recording every episode. It was rarely possible for me to record more than one, or at most two, episodes of a story. The only exceptions being The Evil Of The Daleks and The Web Of Fear, where I managed to get enough tapes to record the whole story.”

Butler’s recordings are still useful however (the reconstruction of The Invasion episodes 1 and 4 uses Butler’s audio of episode 1 and Holman’s audio of episode 4). Wilson’s audios were only discovered recently by Mark Ayres – at this time only recordings for Galaxy 4 and The Daleks’ Master Plan are known to exist, but some of these are complete with continuity announcements.

Full interviews with Graham Strong, David Holman and David Butler can be found in various issues of the Change of Identity newsletters.

BBC Worldwide has since begun releasing these audio recordings again, with linking narration provided by actors playing characters in the story. The Massacre was released in August 1999 and further releases, as well as restored versions of the previous releases, are planned and have continued to emerge ever since. The sound quality of these releases is far higher than the previous BBC releases thanks to the restoration work of Mark Ayres and they are additionally available on CD. Fan-restored versions, taken from the same master recordings, formed the backbone of the reconstructions project. In addition, the redubbed version of The Tenth Planet episode 2 was used on the BBC Video release of the story (BBCV 7030, released November 2000).

Q. What are these cine-clips I hear about? How do they differ from normal clips?

A reel of footage, almost certainly shot by a fan pointing his 8mm cine camera at a domestic TV set during the original transmissions of the Hartnell and early Troughton episodes, began circulating through fandom in April 1996. Because of the differing frame rates of the cine camera and the TV screen, the images on the film are afflicted with some “cut off” interaction between the camera shutter and video scan of the TV which is seen as dark lines that slowly move up the picture, plus typical 8mm vignetting (darkening of the images towards the corners of the screen). The resolution of the camera is poor and hence the images lack detail when compared to professionally-copied clips. Many of the clips are very brief, lasting no more than a few seconds (some last less than half a second) and all of them are of course silent.

The reel is of interest however because of the material included – many classic scenes are only preserved as moving images in this way. Such treasures include Steven’s leaving scene (The Savages episode 4), the prelude to the regeneration sequence (The Tenth Planet episode 4, left), early shots of the new Doctor in the TARDIS (The Power of the Daleks episode 1, left) and scenes from The Macra Terror episode 3 (left). Some stories such as The Myth Makers and The Savages have the only known existing TV material from them preserved in this way – see Steve Phillips’ clips article for full details on what the reel contains, and what other clips are known to exist from missing episodes.

Since its initial rediscovery, the footage has been cleaned up as far as possible by many fans, mostly those also involved in the telesnap reconstructions project. The first fan copies were transferred to video at 25 frames per second (fps), which was about a third too fast in places (this could be established as the reel also contains many scenes from existing episodes, particularly The Chase). It was slowed down to c. 18fps by Michael Palmer who also removed various tints from the raw footage. The other obvious thing to do was to mate the clips up with the correct audio track and this was done by Mal Tanner. The footage was used in many fan reconstructions, particularly Bruce Robinson’s The Savages and Michael Palmer’s The Tenth Planet episode four. It was also instrumental in finally dispelling a long-held fan myth: for many years it was believed that the first episode to feature the new Troughton title sequence (with the Doctor’s face) was The Faceless Ones :1, however the reel contains a 17 second clip of the opening titles to The Macra Terror (from the start of the sequence to the story title caption appearing, probably from episode 3). As can be seen from the third screen grab from the bottom (left), The Macra Terror clearly has the later Troughton title sequence.

It should be pointed out that to preserve the full detail of the image would have required equipment far more powerful than Michael Palmer and Mal Tanner had available. However Mal in particular deserves commendation for his careful research that pinned down accurately the locations within the individual episodes of much of the footage and enabled the appropriate audio track to be added. For some time however, one clip on the reel could not be precisely identified: a scene of Hartnell apparently talking to himself inside the TARDIS. Suggestions that it was from The Daleks’ Master Plan could be quickly discounted as the reel was definitely shot by an Australian fan and Master Plan was not shown in Australia (evidence in support of this is that the camera does not move at all between episodes one and two of The Power of the Daleks – these were shown back-to-back on the same day in Australia). The mystery was eventually solved through careful study and the clip was pinned down to episode four of The Myth Makers – full details are available in issue 13 of The Disused Yeti.

The different sections of the reel (containing clips from different stories, whether existing or not) have different tints which could easily have arisen during the telecine process (for example, the section containing clips from The Chase has a pale brown wash over it, whilst the sections from The Savages and The Power of the Daleks are strongly blue-tinted). The different sections seem to have been shot at different speeds (The Chase clips are way off but The Macra Terror sections are almost at the correct speed, although the camera appears to have been running as slow as 10fps in places) which points to a clockwork camera (fondly remembered for their variable speeds!). A possibility is that two cameras were used (as a roll of film would only last four minutes or so) and that the colour tints arise from shooting on different stocks of film (possibly even some colour and some monochrome film stock). The Doctor Who Restoration Team were able to borrow a fan’s film print of the footage, extracts from which were used the recreate the events surrounding the Doctor’s first regeneration for the BBC Video special release The Missing Years in November 1998 (catalogue number BBCV 6387). Longer clips from the reel were also used on this release.

Q. What are the “censor clips”?

Two distinct batches of material excised from Doctor Who episodes purchased by overseas TV stations for broadcast have been discovered in recent years. Before explaining each find in more detail, a short explanation of the formats each station received the episodes in is needed. When BBC Enterprises originally offered the Hartnell and Troughton episodes for sale to overseas TV stations, the format was 16mm black and white telerecordings (this was partly to avoid the question of which TV system and transmission formats the country used, as film was a universally-accepted medium from which to broadcast). The telerecording process produced a master negative from which the appropriate number of prints could be struck, depending on how many companies wished to purchase the programme in question. The 16mm prints were then supplied to the TV stations that had purchased the programme as their transmission masters. In the case of Australia, strict censorship laws were then in force regarding what could be shown on Australian TV and at what times of day. All new programmes had to be passed before the censors for review and if necessary, editing, before the programme could be transmitted. In the case of Doctor Who, the censors deemed that several scenes had to be cut before the programmes could be transmitted – usually these were scenes of “excessive” violence (such as fights or stabbings, or other death scenes). This was done by physically cutting the film and splicing it back together, and the censorship laws decreed that all material cut had to be kept in government repositories. In 1996 an Australian fan, Damian Shanahan, began researching the days of the censorship laws (which had since been repealed), and with some help from another Australian fan, Ellen Parry, discovered paperwork pertaining to the material that had been excised from early Hartnell episodes of Doctor Who (such as Marco Polo and The Reign of Terror) broadcast by ABC TV Australia – however Shanahan could find no evidence of the cut material and it seems it was destroyed some time previously (evidence suggested cut material had to be preserved for 30 years and then destroyed). He then found more paperwork detailing cuts to later Hartnell, Troughton and Pertwee episodes and followed the trail, eventually coming to the actual film, which had been held in a government archive near Sydney. An interview with Damian Shanahan can be found in Bruce Robinson’s Change of Identity newsletter, issue 5. All the clips discovered in this find are on 16mm monochrome film, as physical extracts from the original telerecordings supplied to ABC TV Australia. (This also means there are no colour extracts in this find from Pertwee episodes that the BBC have no colour copies of).

Between this find and the original process of excising the material, the BBC Enterprises sales copies and the ABC Australia transmission masters had been destroyed, leaving the cut material as clips from episodes which no longer exist in their complete form. When the BBC Archives, and in particular Steve Roberts, found out about the material, they took swift action to recover it and after negotiating some diplomatic obstacles, a copy of all the material was returned to the BBC on a Digital Betacam video cassette (a broadcast standard). As the original means of editing the film prints had been simply cutting and splicing them back together, no account had been taken of the 16 frame offset between the pictures and associated soundtrack present on all 16mm film (originating in the distance between the parts of a projector or telecine machine which reproduce the pictures and those which deal with the optical soundtrack), hence there is an audible click at the start of each clip and the soundtrack runs on for half a second or so at the ends of the clips. The find was very important in providing clips from stories for which very little or no TV material at all was known to exist (such as The Smugglers, The Highlanders and Fury From the Deep) and for helping to fill known cuts in the prints of existing episodes which had been returned from overseas (such as The War Machines). Some of clips make an appearance on the end of the BBC Video release The Missing Years (BBCV 6387, November 1998), and they played an important role in fan reconstruction projects such as the Joint Venture reconstructions of Fury From the Deep and The Wheel in Space.

A further find of similar material came early in 2003. Prominent New Zealand fan Graham Howard was assisting a private film collector with cataloguing some reels of film when a selection of extracts from season five Troughton stories, totalling just over a minute, were discovered. The footage had been cut out of New Zealand broadcasts of the episodes in a similar manner to the Australian clips. Unlike in Australia though, the New Zealand Broadcasting Corporation was not under a statutory obligation to retain the censored extracts. The clips found their way to a private individual as part of a much longer reel of censored material from contemporary programs (including other Doctor Who episodes; these clips being unimportant as the BBC holds complete copies of the episodes in question). Pleasingly, the majority of the clips are from episode 4 of The Web of Fear, a story which relies heavily on visuals for its impact and for which only the first episode was held as TV material prior to this discovery. Full details of these and other clips from missing Doctor Who episodes can be found here. The discovery of these clips does alter the received wisdom concerning NZBC’s censorship policy; it is now clear that they did show cut episodes instead of rejecting an episode outright from screening if it was felt to need cuts making. Howard himself states in an interview that this does leave open the possibility of more missing Doctor Who footage existing in New Zealand. Meantime the clips are available for viewing on the official BBC Doctor Who website (Real Player required) and the clips from The Web of Fear are included in The Reign of Terror box set (BBCV 7335, November 2003).

Q. Is it true that nearly six minutes of Galaxy 4: Four Hundred Dawns still exists?

Yes. The extract (from a 16mm telerecording) exists in private hands and originates round about the time of the making of the 1977 Lively Arts documentary Whose Doctor Who. Several prominent fans were seconded to the production team on an unofficial basis to help choose a selection of clips to be used in the programme. BBC Enterprises at this stage still held their film recordings of all four episodes of Galaxy 4 at their headquarters, Villiers House and it was decided to use a clip from episode one in the documentary. The Doctor Who Appreciation Society attempted to negotiate the rights to re-screen the story at Panopticon II in 1978, but unfortunately whilst this process was going on all copies of the episodes were destroyed by BBC Enterprises – this discovery was one of the major factors in bringing a halt to the junkings. A substantial portion (nearly six minutes) of Four Hundred Dawns was duplicated but eventually it was decided to use only a 30 second clip in the finished documentary from near the middle of the portion duplicated – leaving two substantial offcuts. These were given to the fans concerned (who probably realised that the complete episodes were in danger of being junked at any moment) as a token of gratitude for their help in compiling the programme. For various reasons the footage was not officially returned to the BBC for many years, although a different collector kindly loaned his (somewhat substandard) VHS copy of the footage to the Restoration Team. With the clip used in the finished Whose Doctor Who the footage forms an almost complete sequence from the episode, although as it is actually made up of three separate clips there are slight jumps at the junctions, and a line of dialogue is missing at one such join. The film has now been returned and the extract features as part of The Missing Years – a documentary devoted to the junking and recovery of early Doctor Who episodes which was released in November 1998 as part of The Ice Warriors box set (BBCV 6387, released November 1998). Screen grabs from one copy and precise details on the clips concerned can be found on Steve Phillips’ site. Rumours have abounded in fan circles that the delayed recovery of this footage was an example of “fan hoarding” of missing material (see I hear loads of rumours about private film collectors who have missing material but won’t surrender it) but this is not accurate. The individual in possession of the footage had offered it back to the BBC on several previous occasions but it had been politely declined as the BBC was only interested in complete episodes at the time. Given that complete episode recoveries are now few and far between and the ideal nature of rare clips as extras for DVD releases, this policy has been revised.

Q. What other clips exist from missing episodes?

Many, often through having been featured in another BBC programme that survived the seventies junkings. As a result of the Australian censor clips find and 8mm cine footage, only three stories are now left with no TV material (such as a clip or an episode) known to exist from them: these are Marco Polo, Mission to the Unknown and The Massacre. See Steve Phillips’ clips article and Doctor Who in the Archives pages for full details.

Q. What are these “behind the scenes” pieces of footage from the sixties and seventies that are referred to by people?

Several reels of footage showing work in progress on various stories are now known to exist. There are three very common reels plus two which were a lot rarer in fan “bootleg” circles. The common reels show location work in progress on The Smugglers (shot on 16mm colour Ektachrome film by the owner of the farm being used as the location, durn. 2’37”), The Abominable Snowmen (shot on colour standard 8mm film by director Gerald Blake, durn. 3’26”, though other footage shot by Fraser Hines exists, some of which is included on the re-release of his Myth Makers tape) and The Dæmons (believed to have been shot by a local 8mm enthusiast in Aldbourne, the village which appears on screen as Devil’s End, again on colour standard 8, durn. 6’16”). [Timings are for PAL (European/Australian) video]. The current fan versions of these first three reels circulating are very high quality, and unlike the cine-clips from missing episodes the footage does not suffer from cut-off to any great degree (as it was shot in a conventional manner, as opposed to pointing the camera at a TV screen!). The first two reels appeared on the Mastervision release The Doctors – Thirty Years of Time Travel and Beyond in 1993.

Recent research has cleared up the mystery surrounding two other reels of film, the existence of which had long been rumoured in fan circles. One reel shows studio work in progress on Fury From the Deep which was for a long time believed to have been shot by the director, Hugh David. The other reel shows studio work in progress on The Evil of the Daleks. A VHS copy of these two reels were anonymously sent to the BBC in August 1998, and extracts from both sets of footage appeared on the BBC Video release The Missing Years (BBCV 6387) in November 1998 (see the article on Steve Roberts’ Restoration Team pages on The Ice Warriors Box Set). Working on research for his documentary The Making of Fury From the Deep, which can be found on the JV reconstruction of the story, Richard Bignell discovered that the actual owner of the films was Tony Cornell, a designer who had worked at Ealing Studios and who had shot both films himself. Cornell was contacted and eventually unearthed his original films, allowing the documentary to use the highest quality source available.

Other reels of footage do exist from stories that are not missing from the BBC Archives and it seems others may exist. Footage from existing episodes falls outside the scope of this FAQ and will only be covered briefly. The current tally of other cine reels is as follows:

- The Abominable Snowmen: Gerald Blake’s footage clearly shows another person with a cine camera filming at the same time as Blake. This person may have been a member of the production team, but he has yet to be identified.

- The Abominable Snowmen: Frazer Hines also shot some cine footage during the location filming of this story (included on the re-release of his Myth Makers interview tape).

- Fury From the Deep: It seems possible that some film was taken during the beach sequences; it is not known if this film still exists.

- The Invasion: Location stills clearly show a man filming the Cyberman emerging from the manhole at the bottom of St. Peter’s Hill. Again, it has not been established if this was a member of the production team.

- The War Games: Footage showing filming on the Brighton rubbish tip reportedly exists.

- The Dæmons: A small slice of cine footage exists, shot on 28th April 1971, of Yates and Garvin fighting by the helicopter on the village green. It is unknown if this is an excerpt from a different reel of footage or not. This footage can be found on the original release of Reeltime Pictures’ Return to Devil’s End video documentary. It is possible that a further reel of location work in progress for this story exists – this is currently being investigated.

- The Sea Devils: Local newspaper reports show a naval rating (named as Dave King) holding a cine camera in his hand as he talks to Jon Pertwee. Mr King has not yet been traced.

- The Mutants: The cave mouth scenes were shot at Stonehouse Farm, Kent and the production file for the story includes a letter from the BBC to the then-owner of the farm, a Mrs Castle, responding to a query as to whether it would be possible for her to take some cine footage during the filming. The letter notes that would be all right provided she did not shoot any footage during the actual take. Mrs Castle has been contacted and is currently attempting to determine if she did ever take any footage and if she still retains it.

- The Sontaran Experiment: A local press photo shows a man with a cine camera to his eye.

- Shada: Cine footage appears on the 1993 Mastervision release The Doctors – Thirty Years of Time Travel and Beyond (the full film appeared on a special extended version of the release which was available through Doctor Who Magazine), taken by Stephen Camden (the assistant K9 operator).

- The Leisure Hive: 8mm footage from the Brighton beach sequences exists, also shot by Camden, duration unknown.

- Full Circle: more footage shot by Camden of work underway at Black Park, Buckinghamshire, exists. Camden also tracked down footage shot by one of the professional divers employed to help out with the lake scenes – it was taken by Robin Bierton and it appears to be a single reel of 8mm material.

(UPDATE November 2003: no progress has been made yet on any of the uncertainties listed above and it appears the footage from The War Games may just be rumour. Active efforts are however continuing to research these matters).

Recently (mid-2003) some further material from the studio filming of Fury From The Deep was discovered. It consists of off-cuts from filming (at Easling Studios) for the weed creature attack scenes in episode 6; duration 3′ 32″ and silent. This footage comprises takes not chosen for use in the programme as broadcast and is not therefore a source of clips from the episode. It is expected to feature as an extra on the next BBC DVD release of a Troughton story.

On a similar note, two professional-standard tapes exist from Pertwee era stories, showing studio recording under way and giving a genuine look “behind the scenes” of the stories in question. The first story in question is The Claws of Axos (studio recordings for episodes one and two exist on 2-inch PAL colour Quad videotape). Interestingly this 90 minute tape starts with a title sequence using the working title The Vampire From Space which was abandoned at the last minute in favour of the final transmission title, and the studio recordings include the only PAL material known to exist from episode two (the episode itself exists as a Canadian NTSC videotape converted back to PAL – see Robert Franks’ Archive Pages for full details) This material comprises most scenes in episode 2 apart from those set inside Axos – it was planned to attempt a restoration of the episode for a BBC2 repeat in 2000, by editing this material back in. Unfortunately however, the Doctor Who repeats were been abandoned after only three stories, allegedly due to poor viewing figures, so this work was cancelled along with several other restoration projects. The prospect of future UK repeats of Doctor Who has been mentioned in conjunction with the build up to the transmission of BBC Wales’ revival of the series, however, and this together with the continued release of Doctor Who stories on DVD may see the idea revisited. The other story for which studio recordings exist is Death to the Daleks (a single 90 minute tape exists, containing studio recordings of scenes from all four episodes, on the same format). Such tapes would have existed from all Doctor Who stories but many were wiped as they were considered unnecessary – the two Pertwee tapes managed to slip through the net. Other professional-quality footage exists from Colony in Space (a 20 minute tape of trims from location footage) and Underworld (giving a revealing insight into how the extensive CSO used on that story was executed in the studio).

Q. What are these “telesnaps” and “telesnap reconstructions”?”

Tele-snaps” was a service offered to television production teams or departments by freelance photographer John Cura. For a fee, he would take a series of still photographs off screen during the broadcast of the programme and then make copies available to all interested parties. In the days before home video was a practical prospect, this was one of the only ways that actors, directors and producers could keep a visual record of their work. Full details of the discovery of telesnaps from missing Doctor Who episodes can be found in Bruce Robinson’s Change of Identity newsletter, issue 4. Although “telesnaps” is often used as a generic term for any off-screen photos or screen grabs from television programmes it should strictly be used only to refer to Cura’s work (other people offered a similar service to Cura at the time). Recently telesnaps from The Crusade have been rediscovered, to add to the collection of telesnaps known to exist covering The Gunfighters to The Wheel in Space. In some cases there are sufficient photographs (such as the designer’s record of the sets he constructed, or publicity photos for the likes of Radio Times listings magazines) available from stories that the telesnaps are less important. A good example of this is The Celestial Toymaker.

One point should be cleared up: there is NO POSSIBLE METHOD of recreating a complete episode of Doctor Who from the telesnaps (usually Cura would take about 60 photographs per episode, which represent an accurate description of 60 frames on the original telerecording of the episode – this equates to about 0.16% of the 37,500 frames of a 25 minute programme telerecorded at 25 frames per second). Current morphing techniques have difficulty bridging gaps of 10 frames or so, and it would require enormous technological breakthroughs to contemplate bridging gaps of 500+ frames. All that can be done with current technology is to produce “slide-show” type reconstructions (commonly referred to as “telesnap reconstructions”) as done by fans such as Richard Develyn and Bruce Robinson. Distribution of some of these reconstructions has been discontinued for a variety of reasons but copies are widely available in fandom and the creators of the discontinued productions encourage fans to trade the tapes in the usual manner.

Q. What is this trailer from The Power of the Daleks that people mention?

BBC employee Andrew Martin had decided (in his own time) to review the recordings of programmes retained by the BBC Film and Videotape Library, which had been transmitted live. In particular he was checking the beginnings and ends of such recordings (which were obtained by recording the output-as-broadcast of a BBC television channel rather than simply recording the feed from a television studio) to determine if any extra material had been recorded before the programmes in question began. An important find came in October 2003 when the recording of Beyond The Freeze – What Next? (a political debate show, broadcast November 4th 1966) was ordered up. This 16mm film recording contained a partial copy of a trailer for the next episode of Doctor Who (The Power of the Daleks episode 1, which was transmitted 5th November 1966). It is believed the operator of the film recorder was recording the live output of BBC 1 and before the political show began, decided to test the film recording equipment. The material recorded was the Doctor Who trailer, however the film recorder was stopped and restarted partway through the piece. The usable portion of the extant recording is 36 seconds long, however about 17 seconds of this consists of a “BBC 1 Tomorrow” slide and the Doctor Who title sequence. The remainder (c. 19 seconds) is a professional quality recording of the sequence from near the end of episode 1 as the Doctor, Ben and Polly enter the Dalek capsule. It includes the Doctor’s line “Ben, Polly… Come and meet the Daleks!” and several shots of the new Doctor. Given the non-constant speed of the film recording, much restoration work had to be performed to extract the footage and, as there appears to be no complete audio recording of the trailer on fan recordings of the serial itself (unsurprising, as the trailer was not broadcast before or after an actual Doctor Who episode, so none of the fan audio recordists would have been expecting it) the duration of the complete trailer is not known. The recovered footage can be viewed (Real Player required) on the BBC’s website and it is expected to appear as an extra on a future DVD release.

3.0 Existing episodes

Q. Why weren’t the colour Pertwee stories offered on colour film for overseas sale?

Film recording was an established practice for monochrome productions as a cheap, robust and reliable distribution method for overseas sale. However once colour was introduced, it was also realised that extending the principle to produce colour film recordings of colour broadcasts was not simple. One particular problem is that, if a film recorder of the type used for the production of monochrome recordings is adapted for colour work (by fitting a colour screen and loading it with colour film), undesirable artefacts in the form of severe inteference between the dye grains in the film stock and the phosphor group patterns of the monitor screen are evident on the film recording. In theory, this could be overcome by dividing the monitor into three areas (one for each primary colour of a colour signal, namely red, green and blue), recording the separated colour components onto film in this manner and then reconstructing the original colour signal during later playback of the film recording thus created. The minor drawback of this is that resolution is decreased (as the “same” information has to be stored three times in each frame of film so the effective area for the picture information is reduced to a third of a frame). The major drawback is that it would require extreme care (and more particularly, expense) in aligning and maintaining both the film recorders and the telecine playback devices to overlay the three colour sections with almost 100% accuracy – failure to do so would result in colour fringing, which would be even less acceptable in a broadcast context than the original interference patterns. These technical problems were never overcome since overseas broadcasters upgrading to colour transmissions invested in one of two videotape standards (PAL or NTSC) and it was far simpler to provide them with a colour videotape to transmit from, rather than a colour film recording.

A complete NTSC colour version of The Ambassadors of Death does exist. This was recorded off-air from WNED Channel 17 Buffalo, an American PBS station, for a gentleman named Tom Lundie in 1977. This broadcast was in colour and the serial was one of the very first Doctor Who stories shown by the station. On a technical note, the story was recorded onto Betamax tape, not U-Matic as was long rumoured in fandom! Ian Levine later obtained U-Matic copies of all Lundie’s tapes and these were the versions supplied to the BBC for restoration (and are the source of the long-held fan myth that the original recordings were made on U-Matic tape).

Unfortunately, the recording machine was in Toronto (it seems Lundie paid a friend up there to tape the serial for him, and later bought copies of other colour Pertwee serials off other people) and was attempting to record a New York station – it’s not surprising therefore that the signal was weak. This manifests itself as “rainbows” of colour, most of the time fairly weak and superimposed over the original colour picture (see the images, left). The only episodes not to suffer excessively from this are episodes 1 and 5 (the interference is still present but is not nearly so noticeable). The original 2-inch PAL colour transmission tape for episode one survives and it is far superior in quality to the off-air version of the episode, hence there is no need to colourise this episode. Episode 5 has also been restored to colour by the Doctor Who Restoration Team and has been broadcast on BBC Prime. Episode 6 has also been restored, however it suffers from a brief burst of rainbowing near the beginning of the episode and so is only suitable as a source of colour clips. The colourised versions of episodes 5 and 6 have been transferred to D3 digital videotape and have been given to the Film and Videotape Library at Brentford, however episode 6 is apparently only usable with the permission of the Archive Selector. The vaults of WNED 17 have already been searched; nothing has been found.

The rest of the story is similarly afflicted with colour blurs. Episodes 3 and 4 are very badly affected, as here the rainbows are so strong that the entire colour signal has been lost, and even if the rainbows could be removed the resulting picture would have very little original colour (see left). Removing the rainbows is in itself a very difficult task – the biggest headache is that they are rarely static and their nature changes from scene to scene (sometimes they are diagonal lines across the picture, sometimes they are vertical bars). This means that any algorithm to remove them must be capable of self-adaptation – a difficult thing to program. Two examples of the problem are available, captured from episode 3 of a fan copy of Lundie’s recording. All attempts so far to remove the colour interference patterns have so far been unsuccessful although the BBC do retain a copy of the raw colour version of the serial, derived from the original Betamax tape (albeit a generation removed from it). Despite the picture interference, the raw NTSC colour version of the serial is very watchable. In particular, the sound remains excellent throughout (even when the interference is strongest in episodes 3 and 4). Attempts have been made to establish contact with Tom Lundie but have not been successful. It is almost certain that the colour faults were not introduced during the copying from Lundie’s Betamax recordings to Ian Levine’s UMatic tapes and, even if Lundie still retains his tapes, the degradation of his recordings over 25 years and more makes it highly unlikely that there would be any gain from sourcing colour footage from them.

BBC Worldwide, as BBC Enterprises has become, was keen to complete the range of existing Doctor Who episodes available on BBC Video releases (a task completed with the release of The Reign of Terror box set in November 2003) but the technical problems with The Ambassadors of Death meant it was left until late in the project, partly in the hope that a better colour source may be discovered. Ultimately it was decided that the story should be released on VHS video with as much usable colour as possible being extracted from the Betamax recording to colourise the monochrome film copies, as for the other colourised Pertwee stories. A Restoration Team article describes the process in detail; suffice it to say here that colour sections of usable quality and of length suitable to avoid repeated distracting changes between colour and black and white were used on the final BBC Video release (catalogue number BBCV 7265, released May 2002). Transitions between the formats were handled by cutting directly between them if a scene change coincided with the transition, otherwise a gentle mix in and out of colour footage was employed. Examples include transition from colour to black and white (first video, from episode 2), the opposite effect second, again from episode 2) and a straight cut from colour to monochrome (third, from episode 3). A longer excerpt from episode 3 (final) also shows the faint rainbow colour patterning which was deemed acceptable for the VHS release.

The film recordings of episodes 5 and 6 were treated with VidFIRE processing before the usable colour from the Lundie recordings was overlaid again. The results for episode 5 in particular are highly impressive and worth the purchase price of the release alone.

Whilst on the subject of this story, another frequently asked question concerns the quality of the (monochrome) episode five that often airs, for example on UK Gold and in US syndication. The print is very poor quality with a blurred picture and muffled soundtrack; the UK Gold broadcast often includes a “Do not adjust your set” disclaimer caption. However, the BBC Video release is much better in this respect, especially after the extensive restoration work carried out on episodes 5 and 6 (including making use of the Betamax soundtrack rather than the optical soundtrack on the film recordings). Since the major picture source for this episode is a monochrome film print specially struck for the video release, it is most likely that the BBC Worldwide library master (from where both the UK Gold and US syndication prints are ultimately derived) of this episode was just a poor film print.

Q. The BBC Video release of The Mind of Evil contains a brief extract at the end in colour. I thought the story only survived in black and white?

No complete colour episodes exist from this serial. However three brief colour clips from episode six do still exist. They are:

| Description | Duration (mins,secs) |

| From the beginning of the episode (including opening titles) to Yates telling the Brigadier where the missile is | 3’58” |

| From Jo bringing in a meal for Barnham to Benton’s phone ringing | 0’21” |

| From the Doctor finding the body outside the process room to the Doctor saying “…it’s stronger than ever now!” | 0’15” |

- Timings are for PAL (European/Australian) video, the overall duration in NTSC (North America) is 4’36”.

- On all copies of these clips the picture breaks up during the first and last few seconds of each clip. The picture element of the last clip breaks up before the Doctor speaks his line.

- It has been rumoured for some time that another clip (or a longer version of the final clip) exists, including colour footage of the Keller Machine going wild. These scenes are not present on any fan copies nor were they on the version supplied to the BBC for restoration.

- Other rumours suggest that the colour clips are merely a “teaser” and that Ian Levine possesses a full colour copy of the story. Ian Levine has denied this and further investigations have confirmed Levine is not hoarding any missing Doctor Who material.

- Originally the raw colour footage was used to colourise the appropriate sections of the black and white telerecording of the episode, held by the BBC Film and Videotape Library, in the same manner as the three complete Pertwee stories. This was done in a hurry and the results (extracts from which were used on both More Than Thirty Years in the TARDIS and the UNIT Recruitment Film broadcast before episode six of the 1993 UK repeat of Planet of the Daleks) are not very good. The original BBC copy of Lundie’s raw footage (the quality of which is equivalent to some sections of Doctor Who and the Silurians; i.e. not very good) has since been unearthed and a straightforward standards conversion done on it and was used to colourise the black and white footage again. This is included as a short bonus on the end of the BBC Video release of The Mind of Evil (catalogue number BBCV 6361, released 5th May 1998).

- By the time the serial was broadcast in colour on WTTW it is highly probable that the original BBC colour tapes had already been wiped or destroyed.

- For full details of all the clips known to exist from missing episodes of Doctor Who, see Steve Phillips’ clips article.

The colour clips survive by pure chance. Two competing theories are offered for their existence: either that a full colour off-air copy of The Mind of Evil existed in the hands of a US fan, or that the same fan could only afford enough tape to record extracts from the story.

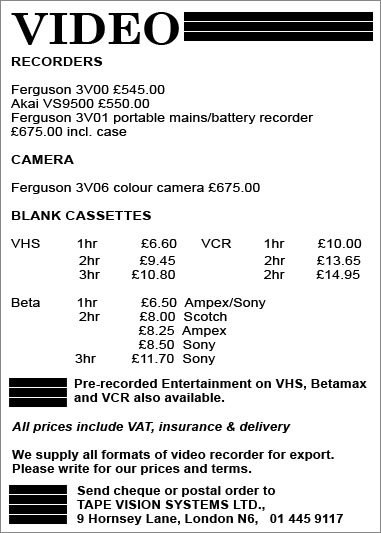

The first theory states that Tom Lundie, the ultimate source for several off-air colour copies of Pertwee stories passed to the BBC via Ian Levine, had in his possession a full colour off-air copy of The Mind of Evil but that he had later taken a dislike to the story and had re-used the Betamax tapes to save the expense of buying new ones (see, above, a 1979 advert detailing UK prices – a good quality 3 hour VHS tape can now be bought for £2.00 or less). According to this theory, episodes 1 to 5 were replaced by an American football match but episode 6 was on a different tape and portions of the beginning of the episode survived because this tape was not rewound fully before being recorded over.

In early 2006, Ian Levine posted on the Restoration Team Discussion forum that he had re-established links with Tom Lundie and denied that the wiping theory was true. According to Levine, Lundie could not afford a further set of tapes to record The Mind of Evil and so only recorded selected clips. This version of events would explain why the colour material that survives from episode six of the story is actually composed of three separate sections, as detailed above.

Q. Bearing in mind that it’s now highly unlikely colour versions of the black and white only Pertwee episodes will turn up, is there any chance that the black and white versions will be computer colourised somehow?

The main problem with computer colourisation is that it is very expensive – the current rate is around US$2000 per finished minute of programme. Actually this works out at only $1.33 per frame, but with 25 frames per second the costs tend to mount up rather quickly. The technique usually carried out is to have a human operator colourise one frame and then to allow the machine to interpret this frame and the colour information in it, and to try to apply it to the next frames, until the operator judges that the results are no longer satisfactory and the process is stopped and repeated. Such a process was used during the colourisation of Doctor Who and the Silurians to overcome a colour fault on the NTSC tape similar to those on various episodes of The Ambassadors of Death, around the junction of episodes five and six, and a sample of The Ambassadors of Death has been colourised in this way. The results are very impressive, but the deciding factor is the cost, and it is doubtful that a video release of The Ambassadors of Death, for example, would give BBC Worldwide a return on its outlay of $200,000 to have the four episodes of the serial that cannot be colourised in the conventional way, restored to colour. The Mind of Evil was released on BBC Video in May 1998 in black and white format and The Ambassadors of Death in May 2002 using as much colour as possible from the defective off-air recordings. It must be remembered that the computer colourisation process has its limitations – where there is no original colour source (such as an off-air recording) to work from, the original colours can only be approximated to, not matched exactly. This would especially be the case for something like a computer colourisation of all six episodes of The Mind of Evil where only a few minutes of original colour footage exist, together with a handful of colour production stills. Whilst cheap colourisation techniques are available, as used for a series The First World War in Colour shown by Channel 5 in the UK in 2003, the results are distinctly unimpressive (skin tones looked rather unreal and clothing worn by different people was all shown in exactly the same colour shade, particularly military uniforms).

Some enquiries were made in late 1999 as to the possibility of colourising the monochrome episodes from Planet of the Daleks and Invasion of the Dinosaurs for repeat on BBC 2. However the Pertwee repeats were abandoned after Doctor Who and the Silurians had completed its run and it seems therefore that the project has been shelved again. BBC Video released Planet of the Daleks in November 1999, however episode three was not colourised, likewise Invasion was not colourised when Invasion of the Dinosaurs was released in October 2003. For the foreseeable future it is unlikely that these episodes will be colourised; the next logical policy review being as and when they are scheduled for release on DVD. Steve Roberts of the Restoration Team believes that costs will remain too high for such a project to be viable, however.

Q. What’s this I heard about a colourised version of Invasion Part One being shown at a convention?

Test work was in progress (see above) on colourising this episode using computer software (Adobe PhotoShop and Premiere mainly, with some help from After Effects and Commotion) and lots of man-hours. Four minutes in total were completed. Initial results were promising but the project is now four years old and advances in computer power in the meantime effectively make the footage obsolete. Far better results could be achieved with up-to-date equipment but the original volunteers no longer have the time to devote to the project.

Q. I hear that an episode of Invasion of the Dinosaurs was junked in mistake for a Troughton episode. Is this true and if so, how did the mistake arise?